Falstaff International

Pink power: the rise & rise of rosé wine

By Anne Krebiehl MW

The rise, swell and sweep of the pink wave is one of the most remarkable reversals of fortune the wine world has seen. Why? Because rosé wines struggled to be taken seriously for the longest time.

While rosés and light, translucent red wines have been around for centuries, in the late 18th and early 19th century they started to lose their lustre. The better red winemaking techniques became, the more paler red and pink wines suffered. Next to fuller-coloured reds, they were seen as weaker in every respect: colour, structure, appeal – and seriousness. The fact that some rosé wines were commercially successful, affordable and popular did nothing to improve that image. Just think of Mateus Rosé. While rosés brought joy to many, their popularity and pricing made them easy to dismiss despite historic styles like Tavel, Bandol and Provençal rosé – all from the south of France. Pink was considered frivolous: why would you age or elevate rosé wine? How could something so beautiful to look at be serious? But now its fortunes have changed. Something happened that shifted the way we think about pink wines. The Observatoire Mondial du Rosé’s report notes a “dramatic” rise of 20 percent since 2002. While France, Spain and Italy still dominate rosé production, South Africa has doubled and New Zealand quadrupled their rosé production. They also note that “the average price of rosé sold around the world continues to climb.” The figures for sparkling rosé are no less impressive, but more of that later.

The turning point

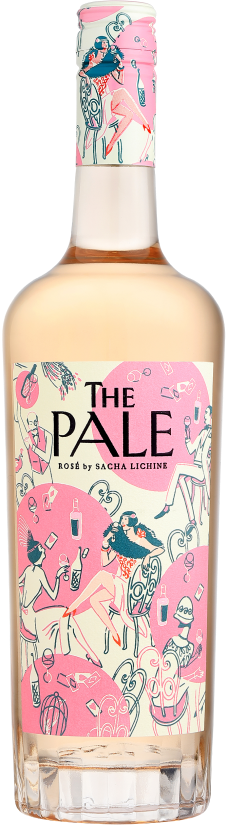

Things had changed by the turn of the millennium: viticulture and winemaking had made immense strides. But, as is often the case, it took outsiders to make a difference. In 2006 Franco-American Sacha Lichine bought Château d’Esclans in Provence. Lichine had deep knowledge of the international wine markets: his father, Alexis Lichine, an influential American wine merchant and author had owned Château Prieuré-Lichine in Margaux, Bordeaux. Lichine junior had an uncanny sense of timing and a singular aim: to make Provençal rosé a fine wine and to create a world-famous brand – Whispering Angel. He made 130,000 bottles of his inaugural 2006 vintage. A decade later in 2016 that had grown to three million bottles and output has grown steadily ever since. A sprinkling of Hollywood stardust also helped Provençal rosé. Celebrity couple Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt bought Château Miraval in Provence in 2008. In 2013 they debuted their 2012 vintage and it became a sell-out. Crucially, both Whispering Angel and Miraval were taken seriously by critics – because they were well made wines.

Provençal pioneers

The combined success of Château d’Esclans and Miraval also turned the spotlight on far more established rosé producers like Domaines Ott. The family had pioneered quality production and their iconic, amphora-shaped rosé bottle had reached cult status among the glitterati on their yachts along the Côte d’Azur – but only niche markets beyond. “My family has been making rosé for more than 120 years now,” says Jean-Francois Ott, general director at Domaines Ott. “The consumer attitude towards rosé has changed significantly. My family has been working tirelessly to raise awareness that rosés can be at the same level as the best white and red wines.” It was Domaines Ott who had perfected that bone-dry, pale elegance that is equated with Provençal rosé today.

“I think that until the 90s, the market for quality rosé was a niche. Today it has expanded significantly, and consumer awareness has increased massively. The real evolution of the category is linked to quality – and that means it is going to last.”

Rosé as a fine wine

Domaines Ott always made a point of expressing their different locations: Château de Selle on limestone, Clos Mireille on schist and Château Romassan on chalk, sandstone and marl. For them, rosé always was a wine that expressed site, like the best red and white wines. However, it was Lichine who took the idea much further by introducing the idea of an ultra-premium rosé. Garrus, the top wine at Esclans, is made mainly from a four-hectare high-altitude parcel of 100-year-old Grenache vines called La Garenne. Lichine also clearly segmented his offer: while Whispering Angel is vinified completely in stainless steel, the next wine up is Rock Angel. Thirty percent of it is fermented in individually temperature-controlled 600-litre oak barrels, the next step up, Château d’Esclans in 50 percent oak while both Les Clans and Garrus, the two top wines, are fully fermented in oak, with the proportion of new oak higher for Garrus. Everyone can taste the difference, the increasing concentration and textural complexity. Illustrating this so clearly enabled Lichine to price the wines accordingly – making Garrus the world’s first rosé wine retailing at over £100. This has since been eclipsed by Gérard Bertrand’s Clos du Temple rosé from Languedoc launched in 2018 but Garrus paved the way for rosé to enter the fine wine market and to be taken seriously as such. It created a whole new category of ultra-premium rosés, like Domaines Ott’s ceramic-aged Etoile, launched in 2020 and Miraval’s oak-aged Muse. Another sure sign of rosé’s elevation to fine wine status was evident in 2019 when global luxury powerhouse Moët-Hennessy acquired both a 55 percent stake in Château d’Esclans and bought another Provence property dedicated to rosé production, Château Galoupet.

Pale, paler, palest

This spectacular reversal of fortunes has not only meant investment in the region but a re-assessment of pink wines across the board. Supermarket shelves now brim in all shades of rosé – even though the vast majority of them aspire to be as pale as the Provençal market leader. Where once existed the misconception that rosé could not be a serious wine, now the idea prevails that a rosé has to be pale in order to be good quality. This could not be more wrong. Rosé wines in every shade of pink – from barely there to lusciously deep – are thus a playground for explorers. Exciting rosés are now made around the world – all we can tell you is to think and drink pink.

Europe’s classic rosés: France

Rosé wines can be made from any red grape. Since rosé wines are made across Europe, from numerous grape varieties, there is a wide spectrum of styles informed by various grape varieties and climates. With 27,219 hectares of vineyards, Provence makes 42 percent of France’s rosé – and 91 percent of Provence production is pink, amounting to more than 150 million bottles.

Provençal rosés are mainly made from Grenache, Mourvèdre, Cinsault and Tibouren but Carignan, Counoise, Cabernet Sauvignon and Syrah are also used, as are white grapes like Clairette, Grenache Blanc and Rolle. The wines are dry and usually pale, capitalising on vivid citrus flavours. Bandol, an appellation within Provence, allows the same grape varieties but is famous for Mourvèdre, a late-ripening, thick-skinned grape, lending structure, spice and ageing potential. Tavel in the southern Rhône is probably France’s most historic and distinct rosé, an appellation dedicated entirely to rosé. Although tiny at just 904 hectares, it was France’s first appellation for rosé wine, given AOC status in 1936. Ernest Hemingway, for instance, was a big fan. Nine grape varieties are permitted and the wines are full-flavoured and deep-coloured, ideal for the robust, southern French flavours of bouillabaisse or grand aioli. If you have only tried pale rosé, you simply must graduate to this gastronomic, complex style. Another Rhône appellation with significant rosé production is Luberon and over in Languedoc, almost a fifth of the wines made are pink – from numerous varieties and across numerous appellations. The Loire valley also has a rosé track record: Sancerre rosé is made from Pinot Noir and is usually delicate, light and bone-dry. Further downstream, other styles take over, at different sweetness levels: Rosé de Loire, Rosé d’Anjou and Cabernet d’Anjou, are variously made from Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Grolleau, Pineau d’Aunis, Gamay and Pinot Noir.

The world’s love affair with rosé is set to continue. Two reasons are paramount: rosé is no longer seen as just a summer wine and has year-round appeal. It has also moved on from perceptions of frivolousness and is enjoyed across genders. You only need to look at supermarket shelves, wine bars or restaurant tables: they shimmer in all shades of pink.